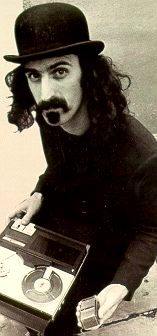

Frank

Vincent Zappa Jr. was born Dec. 21, 1940 in Baltimore of Sicilian immigrants

and lived a mostly normal childhood in Maryland and in Southern California.

Although the Kuder Preference Test administered in sixth grade revealed

that he had a bright future in clerical work, at age 12 Zappa -- who had

always shown a fondness for beating on things -- enrolled in a summer course

in orchestral percussion. Frank

Vincent Zappa Jr. was born Dec. 21, 1940 in Baltimore of Sicilian immigrants

and lived a mostly normal childhood in Maryland and in Southern California.

Although the Kuder Preference Test administered in sixth grade revealed

that he had a bright future in clerical work, at age 12 Zappa -- who had

always shown a fondness for beating on things -- enrolled in a summer course

in orchestral percussion.

Not long after, in a Look magazine article about a Sam Goody record store, he read about an album called Ionization. It was described (in an effort to show Mr. Goody could sell anything) as a dissonant, terrible recording of drums, sirens and animal sounds, and young Zappa made up his mind to find a copy. Writing in 1971 for Stereo Review, Zappa recalled that it took him a couple years, but he finally found the album at a record store while shopping for R&B singles; its actual title proved to be The Complete Works of Edgard Varese, Volume I, and the b&w cover portrait gave the wiry-haired Varese the look of a mad scientist. The record store manager had been using it to demonstrate hi-fi systems, so after a short negotiation young Zappa turned over his bankroll -- $3.80 -- and took the record home. His immersion in the cacophonous work earned him and the family record player banishment to his bedroom, and through his high school years he would make visitors listen to the album as an "ultimate test of their intelligence." His fascination with Varese led him to request, for his fifteenth-birthday present, a long-distance call to the obscure composer, who he correctly guessed lived in Greenwich Village. The two never met, but Varese's sonic experimentation served as an influence thoughout Zappa's career, from blatant sound pastiches such as "Nasal Retentive Calliope Music" and "The Chrome Plated Megaphone of Destiny" (from We're Only In It for the Money) to the capricious ensemble work of Zappa's later career. Zappa played in a few R&B outfits in high school and afterward but made no immediate mark. He met his first wife, Kay, in junior college in 1959 and promptly married her and dropped out. He worked as a silk screener for greeting cards, advertizing copywriter, window dresser, jewelry salesman and door-to-door encyclopedia salesman. By 1962 his marriage had fallen apart, and when he finally received a check for scoring the film Run Home Slow (a cheap cowboy movie written by his high school English teacher) he bought out controlling interest in a tiny, five-track recording studio in Cucamonga, California. He renamed it Studio Z and moved in. Two years later, when R&B singer Ray Collins punched out the guitar player in their band, The Soul Giants (which also included Roy Estrada and Jimmy Carl Black), the guitarist quit, so Collins called on his acquaintance, Frank Zappa, to fill in for the weekend. But Zappa's tenure continued, and before long he suggested the band perform original material, the better to secure a recording contract. The band went along, losing their lounge gigs in the process but picking up dates in Hollywood clubs One night in 1965, Tom Wilson, a staff producer from MGM Records, dropped into the Whiskey-a-Go-Go and saw The Mothers, as they were now named, cranking out a raucous R&B number that, unbeknownst to him, was their sole "boogie" number and hardly representative of the band's material at the time. Thinking he'd discovered a hot white blues band, Wilson offered them a contract and returned to New York. He came west again for the recording session and arrived to hear the band recording "Who Are the Brain Police?" But as the session progressed -- and as the initial shock wore off -- Wilson became enthusiastic; he hustled money from the label for additional sessions, and soon Freak Out!, rock's first double album, hit the streets. At MGM's insistence, however, the band altered its name. Apparently the record executives suspected that "The Mothers" was, well, short for something else. "By necessity," Zappa later wrote, "we became The Mothers of Invention."

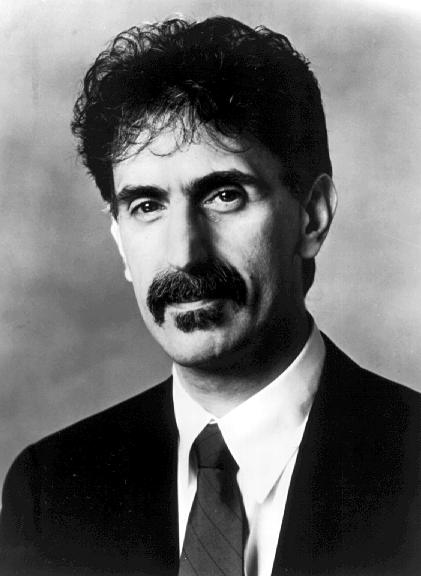

In 1969 he married his second wife, Gail, and with her

produced four children: Dweezil, Moon Unit, Ahmet Rodin and Diva. Zappa

came to national attention in 1985 when he appeared before Congress to

testify against censorship, specifically the record labeling proposed by

the Parents' Music Resource Center, an organization led by, among others,

Tipper Gore. Zappa called the outfit "a group of bored housewives" who

were "treating dandruff by decapitation." Zappa deflated Gore's assertion

that certain types of music could promote deviant behavior. "I wrote a

song about dental floss," he said, "but did anyone's teeth get cleaner?" In his later career Zappa also found time to start an international business-consulting firm, host an interview program on the Financial News Network, and travel to Czechoslovakia, at the invitation of President (and long-time fan) Vaclav Havel, to advise that government on trade and tourism. Frank Zappa died December 4, 1993 of complications resulting from prostate cancer. Including posthumous releases and concert recordings, his body of work spans more than 50 albums and countless bootlegs, and today he is regarded as a significant composer, an innovative musician and a commited social critic. "Without music to decorate it," Zappa once said, "time is just a bunch of boring production deadlines or dates by which bills must be paid." |

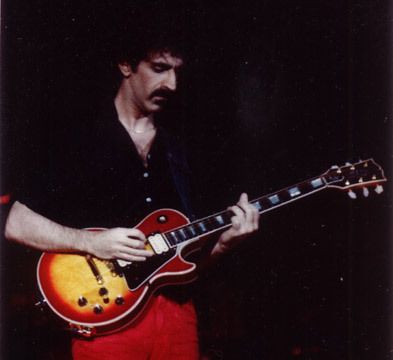

Zappa,

with and without The Mothers, went on to record some of the most brilliant,

scatological, scathing, iconoclastic music of the century, and in a variety

of forms, including doo-wop, psychedelic, jazz, free form and classical

(his orchestral compositions have been conducted by Zubin Mehta and Pierre

Boulez). Determinedly non-commercial, he enjoyed only a cult following

until 1973, when Overnite Sensation produced radio hits like

"I'm the Slime," "Dinah-Moe-Hum" and "Montana," a song about a dental-floss

tycoon. He routinely attracted accomplished sidemen like Steve Vai, Tommy

Mars, George Duke, Adrian Belew, Ruth Underwood, Jean Luc Ponty and Terry

Bozzio. Zappa also founded his own labels and signed acts such as Captain

Beefheart and Alice Cooper.

Zappa,

with and without The Mothers, went on to record some of the most brilliant,

scatological, scathing, iconoclastic music of the century, and in a variety

of forms, including doo-wop, psychedelic, jazz, free form and classical

(his orchestral compositions have been conducted by Zubin Mehta and Pierre

Boulez). Determinedly non-commercial, he enjoyed only a cult following

until 1973, when Overnite Sensation produced radio hits like

"I'm the Slime," "Dinah-Moe-Hum" and "Montana," a song about a dental-floss

tycoon. He routinely attracted accomplished sidemen like Steve Vai, Tommy

Mars, George Duke, Adrian Belew, Ruth Underwood, Jean Luc Ponty and Terry

Bozzio. Zappa also founded his own labels and signed acts such as Captain

Beefheart and Alice Cooper.

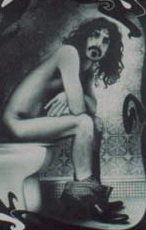

Three

myths plagued Zappa throughout his career. One was that he was the son

of Captain Kangaroo's sidekick Mr. Green Jeans, a rumor that sprang from

his song "Son of Mr. Green Genes," an instrumental on Hot Rats.

A popular poster titled "Phi Zappa Crappa" (left) only encouraged the myth

that he once took a crap onstage (or variations thereof). And thirdly,

despite his outrageous lyrics and eccentric compositions, Zappa never took

drugs.

Three

myths plagued Zappa throughout his career. One was that he was the son

of Captain Kangaroo's sidekick Mr. Green Jeans, a rumor that sprang from

his song "Son of Mr. Green Genes," an instrumental on Hot Rats.

A popular poster titled "Phi Zappa Crappa" (left) only encouraged the myth

that he once took a crap onstage (or variations thereof). And thirdly,

despite his outrageous lyrics and eccentric compositions, Zappa never took

drugs.