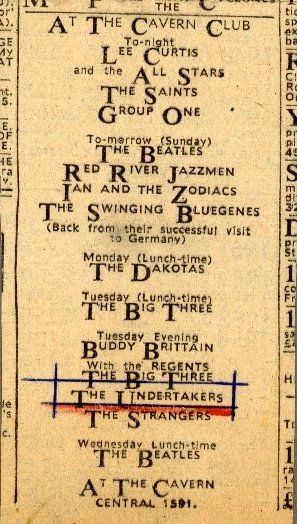

| The

Undertakers, who counted the Beatles among their fans,

were one of more than 300 Merseyside rock and roll

combos but earned a special place in Scouse

hearts. Their sound is summed up nicely in their

allmusic.com entry: "With the saxophone, and the

thumping beat favored during this period, they sounded

very slightly like the Dave Clark Five, but Jones was a

more articulate player than that, and [Huston's] lead

guitar always made the group's sound pretty complex, and

Lomax was an incredibly charismatic soul singer, the

Merseyside rival to Eric Burdon and maybe better than

that. "

The group turned down a management

offer by Brian Epstein and enjoyed limited commercial

success. Their first two singles -- "(Do The)

Mashed Potatoes" b/w "Everybody Loves A Lover," and

"What About Us" b/w "Money" -- didn't chart well,

although the latter rivaled the Beatles' verison, but

their third single, "Just A Little Bit" b/w

"Stupidity," became a Top 20 hit in England during the

summer of 1964.

Dissatisfaction with their producer led

them to leave Pye and move to America, where they

hooked up with New York entrepreneur Bob Harvey and

his partner Bob Gallo, who were also handling Pete

Best. The group endured some rough sledding in

this period, but recorded one single, "I Fell In

Love," written by Bob Bateman, played whatever gigs

they could scrape up, and when not taking a back seat

to the Pete Best Combo, managed to record an album, Unearthed

(1965), which went unreleased for 30 years.

When the money ran out, the Undertakers

went their separate ways, and Huston stayed in

America, carving out an impressive career as an

engineer and producer, working with such talents as

Led Zepplin, the Who, War, the Rascals, Todd Rundgren

, Van Morrison, Blood, Sweat & Tears, Mytch Ryder

& the Detroit Wheels, Ben E. King, the Drifters,

Patti La Belle & the Bluebelles, Solomon Burke,

Mary Wells, Wilson Pickett, John Hammond Jr., James

Brown, ? & the Mysterians, Robben Ford, Eric

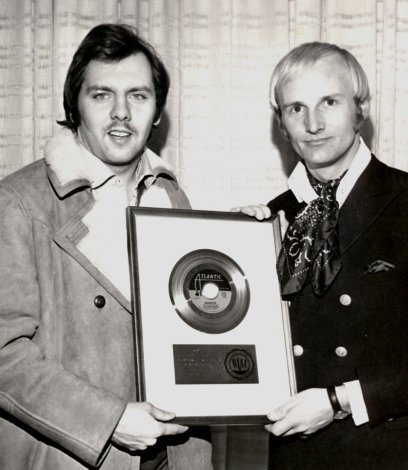

Burden and many more. Among his accomplishments

are several dozen Gold and Platinum records (such as

the gold disc for "Groovin,'" pictured above, with

Rascal Gene Cornish), as well as a Grammy (for War's

"The World Is a Ghetto" ).

In addition to his many years in the

studio, live and remote recording all over the world,

and his work on numerous movie sound tracks, radio and

TV commercials, Huston launched a career as a designer

and acoustic consultant, with projects as varied as

recording studios and control rooms, radio stations,

dubbing and Foley/ADR stages, rehearsal studios, night

clubs, video stages, video editing suites, home

theaters, home studios, restaurants and churches.

Huston also lectures extensively to

architects and designers on acoustics in building

design and residential / industrial noise

control. One of his most satisfying experiences

is his lectures to graduate-student recording

engineers on recording techniques and record

production.

Huston saw Lennon for the last time in

1980, "at the Cherokee Recording Studios, a short while

before he was murdered, actually -- three or four

months. He'd come in to see Ringo. I was in

one studio, producing a session for Lonnie Jordan, the

lead singer of War, for a solo album, and Ringo was

working in another studio. So John comes walking

in with Yoko, and I'm coming out of my control room,

he's in the hallway, and just then Ringo comes out, and

John says, 'Hey Ringo, look who's here, it's Chris

Huston, the Undertaker!' Ringo says, 'I

know, he's been here all week,' So he goes back

into his room, and John and I start talking, you know,

just leaning in the hall for a bit, then we went off

into the lounge and talked for a while . . . with

friendships like that -- I mean, I didn't see him for 15

years, and our lives were so separate, but we had such a

background that you pick up where you left off.

There were never any airs . . ."

Having made his mark in the recording

studios of New York and Hollywood, and all points in

between, Huston now lives in Louisiana. It's

a long way from his beginnings in Merseyside, but he

carries many happy memories of that place and the people

he met there. He still has a creased Polaroid

photo of the Beatles -- with Pete Best and Stuart

Sutcliffe -- rehearsing at the Top Ten Club, taken by

the cigarette girl. "It was a very special time,"

says Huston. "You know, we didn't always realize

it. If I'd known it was going to be important, I

might have taken notes." |

There, too, Huston got to meet many of

his idols, including Gene Vincent (left, with Huston

and Lomax at the Star Club), Ray Charles and Little

Richard. It was Germany, Huston remembers, that

changed the Beatles. "When they came back, it

was like they knew something we didn't know. It

was the strangest feeling . We went to see them,

and they had an energy, they had a fire about

them. I mean, we were all doing,

basically, the same numbers, but there was an

undeniable excitement and look about them."

There, too, Huston got to meet many of

his idols, including Gene Vincent (left, with Huston

and Lomax at the Star Club), Ray Charles and Little

Richard. It was Germany, Huston remembers, that

changed the Beatles. "When they came back, it

was like they knew something we didn't know. It

was the strangest feeling . We went to see them,

and they had an energy, they had a fire about

them. I mean, we were all doing,

basically, the same numbers, but there was an

undeniable excitement and look about them."